I was recently in the waiting room of the Silicon Valley Surgery Center. A young man walked in with his father and approached the desk. They were Chinese, and looked so absolutely different from each other, they caught my eye.

The father was little; he wore a Mao Zedong-style soft cap (minus the star) and a Mandarin collar; he had enough wrinkles to age an entire neighborhood; he walked a little hunched from so much worry and looked at everyone around him with respect.

The son was 17, a head taller and about 20 pounds heavier than his father; he wore spiky hair with enough gel to style an entire neighborhood, T-shirt and baggy pants; he walked a little hunched due to his height insecurity and didn’t look around him at all.

The nurse looked at their paperwork and said apologetically “How do you pronounce your name?” The father started saying a Chinese name, but the son cut him off and said “Just call me Richard.”

In the chair next to me, a young man whispered to his girlfriend “Sellout…” I couldn’t help bursting into laughter, which made the young man embarrassed that I had overheard. I told him “It’s ok, it was funny”, but he felt the need to apologize for his comment.

It made me wonder why so many people in this country Anglicize their names. Most of the time, those who do it are immigrants, and they are simply tired of having to explain their name, or repeat it. I can understand this, as I have long ago abandoned pronouncing the strong, rolled R in my name for the sake of the American pronunciation of Catrina (with a “tree” in the middle of it).

Probably just as often, second and third generation Americans who happen to be named after their family’s original culture also choose to abandon it. One of my husband’s best friends, Japanese, named his son Kazu. It’s pronounced with an emphasis on the first syllable, KAH-zoo. But as early as 2 years old, he was called Ka-ZOO by all the parents and other kids at his preschool. I understand this also. You’re born in America, have grown up American; however hard your family has tried to connect you back to their original country, and however hard you’ve tried… you just don’t feel it; you’d much rather go by Richard.

Now, if you have the un-fortune of having a name that is inappropriate, or bound to be ridiculed in English, I encourage you to change it. I once taught a little girl in an elementary school theatre program whose name was Thitiporn (it means something like “enduring blessings for keeping the law” in Thai). She went by Nancy. But these instances are rare in the overall scheme of things.

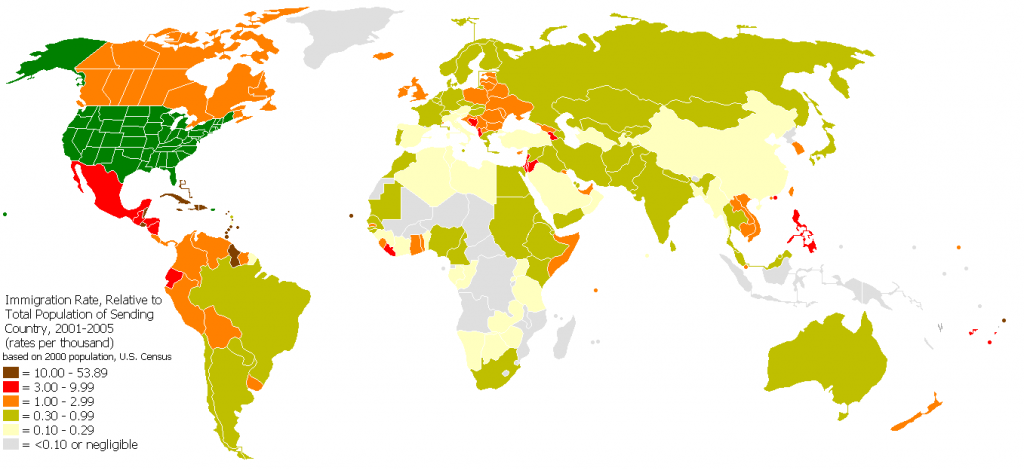

So let’s look at it from a different perspective. America is a big, giant minestrone of races, a luscious ghiveci of nationalities, a colorful fruit salad of religions… you get my drift. All these dishes are good as the sum of their individual ingredients, and not because all the ingredients end up tasting the same in the end – which they don’t. Inter-racial and inter-religious marriages and relationships are becoming the norm. United States citizens are naturalized former citizens of – educated guess – every country in the world (if I’m wrong about this, let me know).

I propose that we all – naturalized or born citizens with non-English names – stop Anglicizing our names. We all know the word “minestrone” because the Italians didn’t change it when they came over and started cooking; so we learned it. Same for “avant-garde”, “Gesundheit”, “fiesta”, “hashish”, “feng shui “, etc.

I humbly add my name to the list, and promise to introduce myself by pronouncing the rolled R from now on. I’m curious to hear your experiences…